Get inspired with the stories of ten whole-life disciples from days of old!

These artists, scientists, campaigners, and entrepreneurs didn’t leave their discipleship on the church steps. From writing symphonies to saving lives, they used the skills and passions God had given them to make a difference right where they were.

Some you’ll know – others, not so much. So, without further ado, let us introduce to you…

This article is one in a series (Culture & Discipleship) from the the London Institute of Contemporary Christianity.

1. Florence Nightingale (1820-1910)

Social reformer, statistician, and nurse

‘God called me in the morning and asked me would I do good for him alone, without reputation?’

You’ve definitely heard of Florence.

Born into a wealthy family, she felt called by God to become a nurse. Despite her family’s protests, she trained in Germany before working at a hospital for wealthy Londoners and volunteering in poorer hospitals treating cholera and typhus.

When news reports from the Crimean War revealed British soldiers were dying of malnutrition and disease, the public outcry was enormous. Until then, women had not been allowed to the front and there were no nurses. But in light of the crisis, Florence’s friend and Secretary of War Sidney Herbert asked her to gather volunteers.

At age 34, she set off with 38 women. Together they saved thousands of lives, with Florence pioneering new standards in hygiene and living standards for wounded soldiers. Working late nights by candlelight, she gained the title ‘The Lady with the Lamp’ and returned home a national hero.

But that wasn’t the end of her service. Despite the news bulletins, there were no official reports on the numbers of dead and wounded. But Florence had the figures. She provided the War Office a detailed breakdown of casualties, using some of the earliest infographics, and recommended best practice for care in future conflict. She continued to campaign in support of improved nursing care and sanitation for decades, including founding a nursing school – the world’s first to be connected to a hospital.

Throughout it all, she dealt with worsening illness and was often bedbound. Even as her physical ability waned, she continued to use her fame, data skills, connections, and training to bring change in the vocation God had given her. And we continue to benefit from her work today.

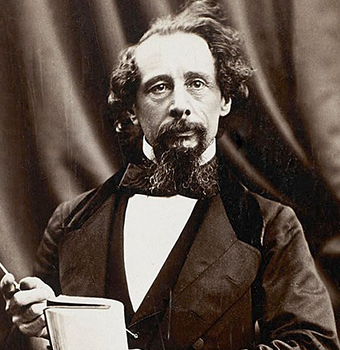

2. Charles Dickens (1812-1870)

Author

‘It is Christianity to... always show that we love Him by humbly trying to do right in everything.’

With his vivid depictions of the best and worst in human nature, it’s no wonder his personal adjective – ‘Dickensian’ – conjures up both twinkly Christmas scenes and dank workhouse misery.

For Charles Dickens, a man of deep if unorthodox faith (big fan of Jesus, not so much of organised religion), writing wasn’t just a way to make money. It was a way to fight for the dignity every person deserves as a child of God – a dignity he himself lost when put to work in a shoe polish factory aged 12.

When he forced his readers to witness Oliver Twist’s hunger, he was asking for their empathy – and demanding action in their own lives. When he invited them into the Cratchits’ loving home, he showed them what ‘Christian gentleness’ looked like – and invited them to follow the example.

But he didn’t just appeal for personal change – he used his books to attack oppressive social systems. After touring brutal Yorkshire schools, for example, he created the evil schoolmaster Wackford Squeers in Nicholas Nickleby to ‘call public attention to the system’.

He hit his mark – in the words of UCL’s John Sutherland, the resulting publicity ‘was instrumental in destroying the Yorkshire school industry’. As the industrial revolution took hold, Dickens’ enormously popular books and tours spearheaded calls for fair treatment for the new working class.

His faith was the foundation of all his work. In the version of Jesus’ life he wrote for his children, he said: ‘No one ever lived who was… so sorry for all people who did wrong, or were in any way ill or miserable’. For Dickens, faith in Christ meant acting out of Christlike empathy, using what was in his hands to improve the lives of others. He summed up that call in A Christmas Carol – arguably the only Christian morality tale still to resonate in post-Christian Britain.

3. Mary Prince (c. 1788-1833)

Anti-slavery campaigner

‘I still live in the hope that God will find a way to give me my liberty. I endeavour to keep down my fretting, and to leave all to Him, for he knows what is good for me better than I know myself. Yet, I must confess, I find it a hard and heavy task to do so.’

Born into slavery in Bermuda in 1788, Mary was sold away from her mother as a child. Forbidden from church by her master, Mary secretly joined a Moravian Church at age 29. There, Mary taught herself to read and learnt that slavery was illegal in Britain itself. Hoping to be freed, she travelled there with her enslavers in 1828. However, it turned out the law was more complicated, and they refused to officially free her.

Instead, in 1829, Mary managed to leave them and sheltered with her church in London. That year, she presented an anti-slavery petition to Parliament, the first woman to do so. But it failed. Many white Brits believed the lies pushed by slave owners – that slaves lived good lives and didn’t want freedom. Mary realised that she could tear down those lies if she told her first-hand experience of slavery.

With help from Susanna Strickland, an author who attended her church, Mary published her autobiography, The History of Mary Prince, in 1831. She didn’t shy away from recounting her heartbreak at being torn from her mother, or the brutality of her life as a slave. Her book sold out three printings in the first year, and Mary’s actions sparked an uproar. Her owner sued for libel and won, despite Mary’s testimony. But her story opened eyes across the country. Two years later, 800,000 slaves living in British colonies were finally set free following an Act of Parliament.

Mary was born into cruelty and brutality, her freedom denied to her. But she knew that God loved and valued her, and that inspired her to keep fighting for herself and others. With help from other Christians, she strove to bring God’s justice in her time.

Image: Megalit on English Wikipedia

4. George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Composer

‘I have read my Bible very well, and will choose for myself.’

After Jesus Christ, the name most associated with ‘Messiah’ must be George Frideric Handel. German-born in 1685, he settled in London at 25 and was fast recognised as a gifted composer with an industrious work ethic to match.

Hardcore Handel fans may argue ‘Messiah’ is not, in fact, his greatest work. And yet the Dublin Gazette‘s take after its debut at the city’s Great Music Hall rings true: ‘Words are wanting to express the exquisite delight it afforded’.

Not everyone loved ‘Messiah’, though. It stirred controversy among church leaders who deemed it inappropriate for an ‘act of religion’ to be performed in a theatre (and by companies of performers rather than ministers of the word!). It wasn’t the first of his works to rile religious authorities: his oratorios ‘Esther’ and ‘Israel in Egypt’ had met with similar opposition.

But Handel’s Christian instincts guided him to challenge this view of ‘secular’ spaces as unfit for his work. ‘I have read my Bible very well,’ he said, ‘and will choose for myself.’ For Handel, there was no sacred-secular divide – no reason why houses of entertainment shouldn’t also host the praises of God. In fact, where better to sing worship than a building dedicated to the wonder of music?

Handel’s faith also spurred his pursuit of excellence. He’s reported to have said he was sorry if he only ‘entertained’ his audience, wishing instead to ‘make them better’. That faith was expressed most explicitly in his final oratorio, ‘Jephtha’. Composed while his vision was failing, it captures both the lament (‘How dark, O lord, are thy decrees’) and hope of the gospel (‘Freedom now once more possessing, Peace shall spread with ev’ry blessing’).

Having worshipped his whole life at St George’s, Hanover Square, Handel was buried in 1759 at Westminster Abbey. His life and work are instructive to any of us who want to pursue God-honouring excellence in our work: be that in churches, concert halls, or wherever we serve.

5. Charles Correa (1930-2015)

Architect

‘Architecture is concerned with much more than just its physical attributes. For our habitat is not created in a vacuum – it is the compulsive expression of beliefs and aspirations that are central to our lives.’

You might not have heard of Charles Correa, but ‘India’s greatest architect’ left his mark all over India’s cities – improving countless lives along the way.

He was born in 1930, raised Catholic, and trained as an architect at the University of Mumbai and MIT. In 1958 he established a practice in Mumbai and set about building a glowing reputation with projects like the Mahatma Gandhi Museum in Ahmedabad. A mere decade later, he was named Chief Architect for the massive new town of Navi Mumbai – giving him control of urban planning for what was to become the largest planned city in the world.

In a role that would affect millions, and guided by his faith, Charles advocated for the needs of the urban poor – rejecting lucrative high-rise developments in favour of low-rise housing, and prioritising community over income per square metre. It was a priority he pursued throughout his career, founding the Urban Design Research Institute to improve quality of life in cities, and pioneering construction of low-cost housing across the developing world.

He recognised the impact architecture could have on a national scale. He championed traditional methods and materials in his buildings, designing structures mindful of India’s natural climate and landscapes. In doing so, he spearheaded a distinctively Indian architecture, breaking with centuries of Western style.

As architect David Adjaye said: ‘His work is the physical manifestation of the idea of Indian nationhood… [he] has that rare capacity to give physical form to something as intangible as “culture”.’ His distinctive, others-focused work has been recognised worldwide, with accolades including a RIBA Gold Medal in 1984 and retrospective in 2013.

Charles saw his profession as an opportunity to represent God’s kingdom on earth, making the places he designed that bit more like heaven.

Image: Dipz99 at English Wikipedia

6. Harold Moody (1882-1947)

Doctor and civil rights campaigner

‘As one of [Christ’s] followers, I must impact to each man, no matter how degraded he may be at the moment... the fact that he was created in the image of God’.

Born in 1882 in Jamaica, Harold Moody committed his life to Christ and decided to become a doctor. Arriving in London in 1904, he graduated top of his class from King’s College – but despite that remarkable feat, no-one would employ him. One institution stated baldly that this was due to his race.

Not to be defeated, he opened his own practice instead, and often treated poor families for free. A man of deep faith, he saw generosity as part of his vocation – serving those who needed help, not just those who could pay.

His other great calling was to anti-racism. Over the years he and his wife Olive, a white nurse, hosted black people visiting London, including leaders from the US, Kenya, Ghana, and Trinidad. He used his standing to help black people facing the ‘colour bar’, confronting employers and officials about discriminatory practices. And in 1931, motivated by his faith, he founded the League of Coloured Peoples to fight for equality in the UK and globally.

He tirelessly campaigned for the rest of his life, all while running his practice and serving in his church. He encouraged black communities, preached to white audiences about the ungodliness of racism, and took the government to task over racist policies. In 1939, when his son was refused a military commission because he wasn’t white, Moody challenged the Colonial Office, securing a change in the law. In 1940, he called for an apology after a BBC presenter used the n-word, setting a new broadcasting standard.

Moody used his whole life and all his gifts to honour Christ. Many of the crises he faced came because he was a black man in a white-majority country. Despite that, he prayerfully and courageously stood for human dignity, practicing compassion even for those who didn’t value him.

7. Octavia Hill (1838-1912)

Early social worker and founder of the National Trust

‘The hill top enables the Londoner to rise above the smoke, to feel a refreshing air for a little time and to see the sun setting in coloured glory which abounds so in the Earth God made.’

Octavia Hill was born into a family of keen social reformers in 1838, encouraged to read and converse with other campaigners (including F.D. Maurice, vicar at St Peter’s Vere Street, where LICC is now based!).

Her father’s business failed, and Octavia, who had been destined for life as a gentlewoman, was sent to train as a glass painter aged 13. She showed skill and dedication, and quickly took charge of the workroom. She also served as a copyist for art critic John Ruskin. When she was 28, he acquired three ‘dirty and neglected’ houses in London, and seeing her leadership skills, asked her to manage them.

From there Octavia continued to buy and manage properties as a way of providing good and stable homes for London’s poorest, only taking a 5% return, rather than the usual 12%. She felt strongly ‘you cannot deal with the people and their houses separately’. Rather than treating tenants as cash cows, she and a team of women used rent visits to get to know them, acting as early social workers and supporting them where they could.

In smoggy London, she was also keenly aware people needed a good environment beyond their homes. Ever the visionary, she rallied with others to save Hampstead Heath and public green spaces in London, arguing everyone had a right to nature, no matter their status.

Each battle with developers proved difficult. How could they protect public beauty in perpetuity? In 1895, with the help of her friend Robert Hunter, a civil servant, and Revd Hardwicke Rawnsley, a campaigner in the Lake District, she founded the National Trust to do just that – and protected the Trust by law in 1907.

Although just one of her many projects, it’s her longest surviving, just as she’d envisioned – today caring for 500 public properties, 125 years on.

8. Kathleen Lonsdale (1903-1971)

Scientist and peace activist

‘I had wrestled in prayer and I knew beyond all doubt that I must refuse to register, that those who believed that war was the wrong way to fight evil must stand out against it however much they stood alone, and that I and mine must take the consequences.’

Born in Ireland in 1903, Kathleen Lonsdale’s scientific brilliance shone through right away. In high school, she took science and maths classes at the local boys’ Grammar School (the girls’ school didn’t offer them) and went on to study physics at the University of London. At a time when higher education was out of reach for most women, Kathleen graduated in 1922 with the highest marks in a decade.

For lots of women, getting married meant the end of their careers. But Kathleen’s husband Thomas supported her ambitions. The couple moved to Leeds, where she worked in the university’s physics department, specialising in crystallography. There, she accomplished the scientific breakthrough that made her name: discovering the crystal structure of benzene.

Kathleen tore down gender barriers in the scientific community, often one of the first women to break into male-dominated spaces. She hit back at the sexist notions that women weren’t suited to the sciences, and that a working mother was ‘abandoning’ her children.

But when WWII broke out, Kathleen faced a dilemma: should she register for civil defence duty, even if it violated her beliefs as a Quaker and pacifist? In the end, she refused to register as a protest, even though her young children would have exempted her anyway, and was imprisoned for a short time.

As it turned out, prison was right where God needed Kathleen to be. When she got out, she joined the boards for several women’s prisons and used her experiences to campaign to make prisons more humane and rehabilitative environments.

When the atomic bomb dropped in 1945, Kathleen joined a number of international peace activist groups. As a scientist, she was horrified by how many of her fellows had been involved with the development of the bomb. She kept campaigning for peace until her death in 1971. Her driving philosophy was ‘act justly, no matter what others may do.’

9. Jesse Boot (1850-1931)

Founder of Boots the Chemist

‘Our great citizen Jesse Boot, Lord Trent. Before him lies a monument to his industry. Behind an everlasting monument to his benevolence.’

At age 10, Jesse Boot’s father died.

And so Jesse left school to help his mother run the family business. In his lifetime, their entrepreneurial spirit and gospel-inspired vision for social change would see Boots the Chemist become a household name.

Let’s set the scene: mid-19th century doctors are prescribing expensive medication that most patients can’t afford. And chemists’ price-fixing policies mean there’s no cheaper option.

Jesse saw the advantage in providing affordable medicine. As well as a savvy business manoeuvre, it was an opportunity to put the family’s faith-based principles into action. So Boots created the ‘Health for a Shilling’ campaign, buying in bulk and selling below the general retail price. As a result, customers could access essential treatment, and Boots expanded to multiple new premises across Nottingham.

In 1885, while on holiday, Jesse met his future wife Florence. She shared his faith and entrepreneurial instincts, and was soon involved in the business. She oversaw the opening of a flagship store with the latest technology: an elevator to showcase multiple floors of goods.

The Boots’ Methodism grounded their business in more than profit-chasing, ensuring they never lost sight of the people they served. They innovated in the workplace: offering employees a doctor’s surgery, college, profit sharing scheme, athletics club, and regular daily breakfast! Boots stores even contained libraries with low subscription fees, and by 1938, 35 million books were being exchanged.

Jesse and Florence were also philanthropists beyond the workplace. They donated upwards of £2m at 1930 prices to charity, and gave land for the new University College at Highfields, now the University of Nottingham.

The Boots show us that turning a profit is a good thing. Their legacy also shows us that turning a profit is not the only thing. And to pursue profit while also pursuing the good of others – that’s God-glorifying business.

10. Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745-1797)

Author and anti-slavery campaigner

‘I early accustomed myself to look for the hand of God in the minutest occurrence … and in this light every circumstance I have related was to me of importance. After all, what makes any event important, unless by its observation we become better and wiser, and learn "to do justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly before God?"'

Imagine England in the 1780s. The Industrial Revolution is just kicking off, changing the reality of everyday life. There is war in the colonies and turmoil brewing in France. The transatlantic slave trade is in full swing, enriching London, Liverpool, and the rest of Britain as hundreds of thousands of people are captured, transported, and exploited.

Enter Olaudah Equiano. Born in Benin (modern-day Nigeria), Equiano had been kidnapped and sold into slavery to an English naval officer. But by his thirties, in the 1780s, Equiano had bought his freedom, learnt to read and write in English, and become a pioneer in Britain’s abolitionist movement. He petitioned Parliament, organised support networks for formerly enslaved people, and founded The Sons of Africa, a political group dedicated to the anti-slavery cause.

In 1789, he published his autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, hoping his story would inspire more people to call for an end to slavery for good. The memoir was hugely successful, with eight editions published during his lifetime. And all throughout Equiano’s story, from slavery to freedom to activism, his underlying conviction of God’s presence is clear: ‘I was sensible of the invisible hand of God, which guided and protected me when in truth I knew it not’.

Equiano’s memoir covers every aspect of his life – from the big events like his emancipation to mundane details like conversations with his friends. He understood that God was with him in everything he’d gone through and everything he was fighting for. After almost two hundred years of oppression, the Slavery Abolition Act was passed in Britain in 1833, just forty-four years after Equiano published his world-changing memoir.

Olivia Haysman-Walker

Communications Assistant

This article is one in a series (Culture & Discipleship) from the the London Institute of Contemporary Christianity.